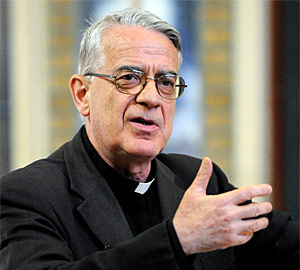

Father Federico Lombardi SJ – the Director of Vatican Radio, the Vatican Press Office and the Vatican Television Centre – delivered the 2009 World Communications Day lecture in London. Speaking on May 21 2009 at Allen Hall Seminary in Chelsea, Fr Lombardi spoke of the challenges and opportunities that the new media landscape presents the Church with – especially the Vatican.

Father Federico Lombardi SJ – the Director of Vatican Radio, the Vatican Press Office and the Vatican Television Centre – delivered the 2009 World Communications Day lecture in London. Speaking on May 21 2009 at Allen Hall Seminary in Chelsea, Fr Lombardi spoke of the challenges and opportunities that the new media landscape presents the Church with – especially the Vatican.

The changes that have taken place in social communications during recent years and decades are obvious to all who have ears to hear and eyes to see.

Communications experts in academia are constantly studying all the phenomena associated with these great changes, and are therefore best placed to discuss the broader picture in abstract generality.

However, I live these changes personally and concretely. I am immersed in the use of various communications media, and so also in their transformations.

I got my start in communications as a writer for La Civiltà Cattolica, a cultural review that continues to publish thoughtful analysis today, just as it did when it was founded 160 years ago. Then I was sent to work in radio, and then to a television production centre; my experience with these media introduced me to, and forced me to come to grips with, the rapid development of communications technology. In order to communicate the relevance of the Christian message to current events, I also had to grasp the ways in which these new technologies were affecting life in the newsroom and behind the editor’s desk.

The advent of satellite distribution systems, particularly for radio, gave us the chance to bring Vatican Radio’s linguistically diverse programming to vastly larger audiences across the world; the introduction of digital production profoundly changed the work methods and the professional profiles of both journalists and technicians. Then came the Internet, and with it new ways of gathering and exchanging information: instantaneous communication via email, and widespread, channelled content distribution on the web.

These past few years at the Vatican Press Office have shown me the need to look for ways to establish a more organic and constructive dialogue and exchange between the communications organs of the Holy See and today’s world of social communications – for today’s communications environment is rapidly becoming something vastly different from that which my generation first experienced it.

In April 2009, a document prepared by Microsoft entitled ‘Europe Logs On: European Internet Trends of Today and Tomorrow’, offered the following piece of information: if it continues to grow at the projected rate, then by June of 2010 internet use will surpass traditional television use among European consumers, reaching an average of more than 14 hours per week, to television’s 11.5.

In 2008, the Internet surpassed all other media except television as the principal source of information for national and international current events. Its rise continues and seems unstoppable.

I consider myself interested in and responsible for many different vectors of communication in the Church – for communication to many different countries where a wide array of situations are to be encountered and where a broad spectrum of different circumstances obtain. I am well aware that in a large part of the world, communication happens in ways that are very different from those found in more developed countries. It is also true that even in the more developed countries, there are palpable differences that need to be taken into account. The document I just cited speaks of a ‘digital divide’, separating North from South as far as internet access and use is concerned.

From the Church’s point of view, leaving those with fewer possibilities on the margins is simply not an option. For us, the poor and developing countries are at least as important as the wealthy, if not more. So, we cannot leave the traditional technologies and forms of communication by the wayside, for they are still necessary to serve a large part of humanity. At the same time, we cannot but be attentive to the direction in which communications are moving, nor can we allow ourselves to lose touch with the latest advancements in the world of communications.

Reflection and debate regarding the way the Church communicates both internally and externally – that is, with her members and with the larger world – have intensified recently, not only because of discussions about the Pope and the Church, but also because of the way those discussions were conducted. The coverage was widespread and just about every news outlet took an editorial stance at one point or another. Throughout it all, many different issues got confused, but no one can doubt that the whole business did raise some very real questions. It is our job to get to the bottom of those questions and then figure out something useful to say about them.

Shockwaves

A first and obvious consideration regards the speed and intensity with which news spreads, especially sensational news. Internet communications have greatly increased both the speed with which the shockwaves spread, and their reach. Communication happens around the clock, 24/7. News no longer reaches people to the rhythm of the morning paper or the TV bulletins.

Additionally, the vast and ever-growing variety of voices makes it more and more difficult to attract people’s attention, and this results in the tendency to sensationalise news, to ‘spice up’ the headlines. Many journalists and news outfits are endlessly searching for the next big scoop, as though getting it were the one thing that, in the midst of the great sea of words and images, can give their existence some sort of affirmation.

We are all aware of this situation, and we see the continuous risks, but we can’t seem to understand how to fix it.

Let’s consider more closely some recent cases, like Pope Benedict XVI’s Regensburg discourse, the Bishop Williamson affair, or the controversy over Pope Benedict XVI’s statements regarding condoms and the spread of HIV and AIDS in Africa.

Sensational reaction to each event came quickly, ranged broadly and penetrated deeply.

Answers to these critiques were not lacking. They came not only from me through the Press Office of the Holy See, but also from voices well-disposed to the Church. These responses, however, were neither as numerous nor as ‘media-friendly’ as the voices of the critics that occasioned them, and, though they were not overly slow in coming, they were nevertheless in a certain sense rather late, with respect to the surprise effect of the original shockwave.

Once the first wave of criticism had passed, though, people were able to do some hard thinking – and they did. The subsequent reflections were serious, penetrating and well-argued; it took a while for word of them to make its way through the communications channels and reach the public, but eventually the public did hear about and really benefit from these contributions to the discussion.

I am convinced that the question of Christian-Muslim relations has been addressed more frankly, more seriously and with greater depth after Regensburg than before; that the clamorous response to the declarations of Bishop Williamson not only allowed us to make the true positions of the Pope and the Church regarding the Holocaust to be more widely known and clearly understood, but also served to strengthen Catholic-Jewish relations and dialogue; that there is real hope that re-establishment of the conversation with the followers of Archbishop Lefebvre might lead to a deeper and more balanced reading of Vatican II in the direction of a hermeneutic of renewal in continuity with the Church’s Tradition; that the debate over condoms is leading to greater understanding and awareness of what truly effective HIV/AIDS prevention strategy is in Africa and elsewhere.

I would like at this point to make something clear: I am not saying that everything we have done and are doing vis à vis Vatican communications is perfect. I do think, however, that in a world such as ours, we would be deluding ourselves if we thought that communication can always be carefully controlled, or that it can always be conducted smoothly and as a matter of course.

Is there any great institution or personality that, finding itself constantly in the limelight, is not the object of frequent criticism? We have dozens of ready examples in Presidents and Prime Ministers – why ought we to think that the Pope or the Church, in a secular world such as ours, ought to be an exception?

Whenever we face sensitive topics, we must inevitably proceed dialectically, from the statement of the position, to criticism, to a clearer and more penetrating response. It is a mistake to think that we ought to avoid debate. We must always seek to conduct debate in a way that leads to a better understanding of the Church’s position, and we must never get discouraged.

We might add that the way such debates unfold is new, as well. Debate is no longer generally driven by the contributions of a few well-known, trusted and easily recognizable voices, for example the op-ed writers of the major newspapers. The chorus of voices that take part in debate over issues today is much larger and more diverse; the membership of that chorus transcends the traditional limits of language and culture, it is indeed international and even global.

So, we need to look further afield, and we also need to broaden our outlook. Today we approach the problem from the specific point of view of the Church, or of the Pope’s image, or of the Christian truths we desire to proclaim. The problem, however, is not ours alone. It would be ridiculous to think so. It is a general problem, involving the family and the institutions of the state and civil society. The problem regards the ability to have and to maintain sound points of reference in the flow of communications in the world.

In seeking the right road for the Church, we are also looking for those roads, which might be interesting and useful for everyone.

Living in this world

We all live in the same world, and the Church teaches us to look on this world realistically – but She also teaches us to view the world with trust, and above all, with love.

The positive tone of the whole teaching of the Church on social communications is striking. Just look at the names of the magisterial documents: Miranda prorsus, Inter mirifica (‘Among the wonderful’), Communio et progressio – even the message with which Pius XI inaugurated Vatican Radio in 1931 is full of expressions of trust in the ability of the radio to serve the cause of good in the world.

Inspired by this Magisterial teaching, we have always sought to make the best possible use of the available tools – the ‘traditional’ tools of communication, if you will – but now we find ourselves immersed in a new stage of our journey.

To be sure, we have to be aware of the risks and the ambiguities that attend this stage, the enormous potential for manipulation and moral corruption that are nested in modern social communications. As potential for use increases, so does the potential for misuse.

As we know unless we are naïve, the internet presents very grave risks, and poses crucial formative challenges that no one – not families, not schools, not society as a whole – may ignore. There is also great potential for good, and the Church’s attitude encourages us to recognise this potential in its every manifestation, and to insert every good element possible into the wide world of communications, like the wheat that grows in the field along with the darnel.

The Pope’s message for this year’s World Day for Social Communications is in this sense an exemplary document and a rich source for reflection and encouragement. Titled, New Technologies, New Relationships. Promoting a Culture of Respect, Dialogue and Friendship, the message is driven by a fundamental strategic insight: the need to speak to ‘the digital generation.’

The Pope knows that the Church will be an efficacious presence in the world that is taking shape only to the extent that She succeeds in keeping the truths of the faith in close touch with the emerging culture and the younger, growing generations. This is why he puts such emphasis on relationships: ‘new technologies, new relationships.’

The whole world of social communications is concerned with relationships: among persons, groups, whole peoples – but just which relationships do we want to nurture and develop? What substance and to what end? In what spirit?

The impressive development of social networks, of content and information exchange, of the desire to comment on and intervene in every discussion of every topic, tells us that the internet has given rise to an omni-directional flow of transversal and personal communications, the scope of which was unimaginable until very recently.

One of the biggest challenges facing us at present is that of interactivity, and, I would say, of ‘positive interactivity’. How ought we to tackle this challenge at all levels of the Church’s life? For me specifically, the challenge presents itself to the communications efforts of the Holy See, and our experience at Vatican Radio comes to mind. In recent years the internet has been an important tool that has made it possible for us to deliver content to countless users of all kinds. Now, however, the reality of the situation that is emerging is one in which the great thing is not simply content distribution, but increasingly greater interactivity.

This is an extremely complex and difficult area that requires enormous commitment of all kinds of resources. Being able to receive comments is not enough: we need to develop a structural capacity to respond clearly and competently to the questions that arise, and that takes manpower, time and money.

At the end of January this year, in partnership with Vatican Radio and CTV (the Vatican Television Centre), we opened a YouTube channel with regular video news broadcasts in four languages. At Easter, we broadcast the whole of Pope Benedict XVI’s Easter Message with complete subtitles in 27 different languages – that’s a YouTube record, by the way! We are on our way towards an active Internet presence, though for the moment it is a basically one-directional presence, and will be until we understand the best way to establish interactive dialogue with our visitors.

For me, the problem is profound and serious – it is, in a certain sense, an ecclesiological problem. I mean to say that we at Vatican Radio and CTV worked hard to develop a successful strategy that integrated our Rome-based service with the Catholic TV and radio stations throughout the world. We built a network through which we provide information and programming that deal with the Church on a universal level, while regional and national Catholic stations provide coverage of their respective areas. We created a communications network that mirrors the structure of the Church and the various levels of service to the Church, from the Pope to the Bishops’ Conferences to the diocesan level, always seeking to promote integration and dialogue while respecting the different levels of competence and responsibility.

Just as we began to congratulate ourselves on our success, the Internet came along and began destroying, or at least confusing this logic of distinction and complementarity of levels! Internet navigators move more freely in the global network and do not hesitate to speak directly to people and institutions on all levels, wherever they find them.

The offices of Chancellor Merkel and President Obama are working to develop Internet services aimed at responding to queries from individual citizens; several dioceses and Bishops’ Conferences have similar initiatives. Should the Vatican, too, be working in this direction on a global level, and if so, how? How can we correctly promote the presence of the Pope in the life of the whole Church – that is, how can we use this technology to make his presence felt in the local Churches throughout the world without contributing to the creation or growth of a centralistic mentality that is not only inopportune, but at loggerheads with the right articulation and proper autonomy of the local Church? Deep down, I realise that the small step we have taken with YouTube is just the beginning of a long journey, and that our next steps must be taken with trust, and also with prudence.

We must not be of this world

In our service to the Church, we need to be constantly asking ourselves whether the limits and defects of our own communication skills in any given moment are making it more difficult for others to understand the Church’s message, so that they reject it, or whether the message itself is being rejected even though it has been understood – or precisely because it has been understood.

We are called to be witnesses to God’s love for humanity and for this world, but we cannot hide from the fact that the Gospel of Christ often becomes a sign of contradiction during the course of the vicissitudes of the world.

We cannot fool ourselves into thinking that a perfect communications strategy could ever make it possible for us to communicate every message the Church has to offer in a way that avoids contradiction and conflict. Truth be told, success in this sense would be a bad sign – at the very least, it would indicate ambiguity or compromise, rather than authentic communication.

I am convinced that in the present Pope and in his predecessor – and doubtless in others that came before them, as well, though I will speak of Benedict and John Paul II because I know them better – we have had and continue to have two eminent witnesses of the courage to speak the truth, to be oneself, and not to become enslaved to the desire for approval, which is one of the greatest idols of the modern world and of contemporary communications.

It is important to realise that many of the things the Church says – and that we should say if we would be faithful to Her – go against the grain. We need to hope that this is the case, not because we are outmoded or out of touch with the times in which we live, but because the Gospel of Christ is itself often against the grain.

To preach forgiveness in situations of hate and desperate conflict is against the grain. To preach a vision of human sexuality rooted in love and responsibility is against the grain.

To preach hope for a life beyond death to a world that is closed in on itself is against the grain, as is every concrete, everyday choice to live in faithfulness to Christ and His Church, a faithfulness founded on precisely that hope, which sees beyond death and yearns for eternal life.

Here we come to the very heart of communications in the Church, the heart of the Church’s mission of communication to and for the world. The ‘hard core’ that is strong enough to resist the trials and travails of history, is the credibility of the Gospel message, the authoritative character of the message that comes from authentic witness to the faith in the lives of the faithful. I am convinced that much of the respect that John Paul II earned from the world and from professional communicators, was at the end of the day a consequence not so much of his charisma as it was of his personal credibility. He was long criticised as a conservative, a retrograde, the ‘old Polish fellow’ unwise to the ways of the modern world and modern ideas, but at the end he was respected as a man of courage and integrity, firmly rooted in his faith and able to bear personal witness to it through all the different trials he faced during his long life.

Pope Benedict XVI has a very different personality, but no one can doubt his integrity and his intellectual and spiritual coherence. From these come his courage unabashedly to take and to maintain positions that are unpopular for those who have embraced the dominant culture. Think of his recent letter to the bishops; it is a most personal and admirably courageous communication. He expresses himself in the first person, repeating and defending the priorities and the criteria of action that he has set out for his pontificate, and leaves no room for doubt that his choices, as a generous search for reconciliation, have their deepest inspiration from the Gospel.

A few weeks ago, a journalist asked me to share my thoughts on good and evil in communications. In particular, he asked me to identify the principal faces of evil in our work and in the flow of communications.

It is easy to paint the big picture. The hard part is recognising the real, concrete, individual cases and situations, and then to put people on their guard, especially those most susceptible to the blandishments or tricks of evil.

There is the classical face of falsehood, more or less explicit, and often mixed with half-truths, motivated by interests of different kinds. It always aims to deceive.

There is the face of pride, of self-referencing self-centeredness that despises his fellows and refuses to listen to other positions, but seeks always and only the absolute affirmation of the superiority of his own position.

There is the face of oppression and injustice, that would deny his fellows’ freedom to gather information and give expression – the face of injustice that denies the voice of his fellows and so denies their basic human dignity and their rightful place in society.

There is the face of debauched sensuality that seeks to use and possess, and has respect neither for the body nor for the image of the other. This face expresses the materialistic hedonism that turns persons into brutes.

There is the face of escapism, which, seeking refuge in imaginary or virtual worlds, completely subverts the purpose of the new communications technologies, making them a source of isolation and slavery.

There is the face of division, that seeks to demolish dialogue, to undermine all efforts at mutual understanding among people of different creeds and cultures, and to set them against one another rather than to help them come together in genuine appreciation. This face becomes the face of conflict and war.

We need to learn to recognise these faces of evil for what they are, in order to make communications freely able to serve the good, that is, to further the construction of a culture of respect, of dialogue and friendship, and to place the immense potential of contemporary communications in the service of communion in the Church and of the unity of the whole human family.

Communication for communion: communicating with a view to unity.

This is the best expression I can find of my vocation as a communicator, of our vocation as communicators.

I have learned the need to discover ever anew the difficulties and the struggles of this vocation, and also the beauty and the greatness of it.

There is one precise moment that remains fixed in my memory, an unexpected illumination, in which, after many years, I understood the nature of the call to communicate.

There was a young people’s prayer gathering in the Paul VI Audience Hall, in which an aged John Paul II was taking part. CTV had set up ten or so different two-way satellite links so that young people in other European cities could take part in the broadcast.

Watching the giant screen in the Hall, the Pope saw the various other gatherings; he heard the young people’s greetings and greeted them in turn. We were all more than a little tense, owing to the complexity of the technical side of the operation – I remember because I was crammed in a tiny tech van with all my CTV colleagues and was sweating buckets.

At one point the Pope, with his characteristic spontaneity, said, ‘What a marvellous thing is this television! I can see and speak with my young people in Krakow as though they were right here. Blessed be television!’ I was stunned.

Think of all the terrible, awful things that television does, and now the Pope is calling it blessed! But he was right, of course. He sees further, for television really can create communion, it can allow the Pope and the whole Church, as it did that evening, to experience the joy of communion, and this is proof that television can be used for good, that it can truly be blessed! But this depends on us. We are the ones who must make television a source of blessing, and not leave it to become an instrument of corruption.

This, then, is my vocation – our vocation: we are called to make sure that the press, the radio and television are tools and paths toward blessedness. Now, I shall have to work more, all of us shall have to work even harder, so that every day it will be more and more true to say, and so that we might be able to say with greater and greater conviction: the internet is truly blessed!