HOMILY OF HOLY FATHER FRANCIS ON THE OCCASION OF THE FEAST OF SAINT IGNATIUS

HOMILY OF HOLY FATHER FRANCIS ON THE OCCASION OF THE FEAST OF SAINT IGNATIUS

Church of the Gesù, Rome

Wednesday, 31 July 2013

In this Eucharist in which we are celebrating our Father, Ignatius of Loyola, in the light of the Readings we have heard I would like to suggest three simple thoughts, guided by three concepts: putting Christ and the Church at the centre; letting ourselves be won over by him in order to serve; feeling ashamed of our shortcomings and sins so as to be humble in his eyes and in those of our brethren.

1. Our Jesuit coat of arms is a monogram bearing the acronym of “Iesus Hominum Salvator” (IHS). Each one of you could say to me: we know that very well! But this coat of arms constantly reminds us of a reality we must never forget: the centrality of Christ, for each one of us and for the whole Society which St Ignatius wanted to call, precisely, “of Jesus” to indicate its point of reference. Moreover, at the beginning of the Spiritual Exercises we also place ourselves before Our Lord Jesus Christ, our Creator and Saviour (cf. EE, 6). And this brings us Jesuits and the whole Society to be “off-centre”, to stand before “Christ ever greater”, the “Deus semper maior”, the “intimior intimo meo” , who leads us continuously out of ourselves, leads us to a certain kenosis, “to give up self love, self-seeking and self-interest”; (EE, 189). The question: “is Christ the centre of my life? For us, for any one of us, the question do I truly put Christ at the centre of my life?” should not be taken for granted. Because there is always a temptation to think that we are at the centre; and when a Jesuit puts himself and not Christ at the centre he errs. In the first Reading Moses insistently repeats to the People that they should love the Lord and walk in his ways “for that means life to you” (cf. Dt 30:16, 20). Christ is our life! Likewise the centrality of Christ corresponds to the centrality of the Church: they are two focal points that cannot be separated: I cannot follow Christ except in the Church and with the Church. And in this case too we Jesuits — and the entire Society — are not at the centre, we are, so to speak, a corollary, we are at the service of Christ and of the Church, the Bride of Christ Our Lord, who is our holy Mother the hierarchical Church (cf. EE, 353). Men rooted in and founded on the Church: this is what Jesus wants us to be. There can be no parallel or isolated path. Yes, ways of research, creative ways, this is indeed important: to move out to the periphery, the many peripheries. For this reason creativity is vital, but always in community, in the Church, with this belonging that gives us the courage to go ahead. Serving Christ is loving this actual Church, and serving her generously and in a spirit of obedience.

2. What road leads to living this double centrality? Let us look at the experience of St Paul which was also the experience of St Ignatius. In the Second Reading which we have just heard, the Apostle wrote: I press on toward the perfection of Christ, because “Christ Jesus has made me his own” (Phil 3:12). For Paul it happened on the road to Damascus, for Ignatius in the Loyola family home, but they have in common a fundamental point: they both let Christ make them his own. I seek Jesus, I serve Jesus because he sought me first, because I was won over by him: and this is the heart of our experience.

However he goes first, always. In Spanish there is very expressive word that explains it well: El nos “primerea”, he “precedes” us. He is always first. When we arrive he is already there waiting for us. And here I would like to recall the meditation on the “Kingdom in the Second Week”. Christ Our Lord, the eternal King, calls each one of us, saying: “to anyone, then, who chooses to join me, I offer nothing but a share in my hardships; but if he follows me in suffering he will assuredly follow me in glory” (EE, 95); to be won over by Christ to offer to this King our whole person and our every endeavour (cf. EE, 96); saying to the Lord that we intend to do our utmost for the more perfect service and greater praise of his Majesty, putting up with all injustice, all abuse, all poverty (cf EE, 98). But at this moment my thoughts turn to our brother in Syria. Letting Christ make us his own always means straining forward to what lies ahead, to the goal of Christ (cf. Phil 3:14), and it also means asking oneself with truth and sincerity: what have I done for Christ? What am I doing for Christ? What must I do for Christ? (cf. EE, 53).

3. And I come to the last point. In the Gospel Jesus tells us: “whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake, he will save it…. For whoever is ashamed of me…” (Lk 9:23; 26). And so forth. The shame of the Jesuit. Jesus’ invitation is to never be ashamed of him but to follow him always with total dedication, trusting in him and entrusting oneself to him. But as St Ignatius teaches us in the “First Week”, looking at Jesus and, especially, looking at the Crucified Christ, we feel that most human and most noble sentiment which is shame at not being able to measure up to him; we look at Christ’s wisdom and our ignorance, at his omnipotence and our impotence, at his justice and our wickedness, at his goodness and our evil will (cf. EE, 59). We should ask for the grace to be ashamed; shame that comes from the continuous conversation of mercy with him; shame that makes us blush before Jesus Christ; shame that attunes us to the heart of Christ who made himself sin for me; shame that harmonizes each heart through tears and accompanies us in the daily “sequela” of “my Lord”. And this always brings us, as individuals and as the Society, to humility, to living this great virtue. Humility which every day makes us aware that it is not we who build the Kingdom of God but always the Lord’s grace which acts within us; a humility that spurs us to put our whole self not into serving ourselves or our own ideas, but into the service of Christ and of the Church, as clay vessels, fragile, inadequate and insufficient, yet which contain an immense treasure that we bear and communicate (cf. 2 Cor 4:7).

I have always liked to dwell on the twilight of a Jesuit, when a Jesuit is nearing the end of life, on when he is setting. And two images of this Jesuit twilight always spring to mind: a classical image, that of St Francis Xavier looking at China. Art has so often depicted this passing, Xavier’s end. So has literature, in that beautiful piece by Pemán. At the end, without anything but before the Lord; thinking of this does me good. The other sunset, the other image that comes to mind as an example is that of Fr Arrupe in his last conversation in the refugee camp, when he said to us — something he used to say — “I say this as if it were my swan song: pray”. Prayer, union with Jesus. Having said these words he took the plane to Rome and upon arrival suffered a stroke that led to the sunset — so long and so exemplary — of his life. Two sunsets, two images, both of which it will do us all good to look at and to return to. And we should ask for the grace that our own passing will resemble theirs.

Dear brothers, let us turn to Our Lady who carried Christ in her womb and accompanied the Church as she took her first steps. May she help us always to put Christ and his Church at the centre of our life and our ministry. May she, who was her Son’s first and most perfect disciple, help us let Christ make us his own, in order to follow him and serve him in every situation; may she who responded with the deepest humility to the Angel’s announcement: “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord; let it be to me me according to your word” (Lk 1:38), enable us to feel ashamed at our own inadequacy before the treasure entrusted to us. May it also enable us to feel humility as we stand before God; and may we be accompanied on our way by the fatherly intercession of St Ignatius and of all the Jesuit Saints who continue to teach us to do all things, with humility, ad maiorem Dei gloriam, for the greater glory of our Lord God.

HOLY MASS ON THE LITURGICAL MEMORIAL OF THE MOST HOLY NAME OF JESUS

HOLY MASS ON THE LITURGICAL MEMORIAL OF THE MOST HOLY NAME OF JESUS

HOMILY OF POPE FRANCIS

Church of the Gesù, Rome

Friday, 3 January 2014

St Paul tells us, as we heard: “Have this mind among yourselves, which was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant” (Phil 2:5-9). We, Jesuits, want to be designated by the name of Jesus, to serve under the banner of the Cross, and this means: having the same mind as Christ. It means thinking like him, loving like him, seeing like him, walking like him. It means doing what he did and with his same sentiments, with the sentiments of his Heart.

The heart of Christ is the heart of a God who, out of love, “emptied” himself. Each one of us, as Jesuits, who follow Jesus should be ready to empty himself. We are called to this humility: to be “emptied” beings. To be men who are not centred on themselves because the centre of the Society is Christ and his Church. And God is the Deus semper maior, the God who always surprises us. And if the God of surprises is not at the centre, the Society becomes disorientated. Because of this, to be a Jesuit means to be a person of incomplete thought, of open thought: because he thinks always looking to the horizon which is the ever greater glory of God, who ceaselessly surprises us. And this is the restlessness of our inner abyss. This holy and beautiful restlessness!

However, because we are sinners, we can ask ourselves if our heart has preserved the restlessness of the search or if instead it has atrophied; if our heart is always in tension: a heart that does not rest, that does not close in on itself but beats to the rhythm of a journey undertaken together with all the people faithful to God. We need to seek God in order to find him, and find him in order to seek him again and always. Only this restlessness gives peace to the heart of a Jesuit, a restlessness that is also apostolic, but which must not let us grow tired of proclaiming the kerygma, of evangelizing with courage. It is the restlessness that prepares us to receive the gift of apostolic fruitfulness. Without restlessness we are sterile.

It was this restlessness that Peter Faber had, a man of great aspirations, another Daniel. Faber was a “modest, sensitive man with a profound inner life. He was endowed with the gift of making friends with people from every walk of life” (Benedict XVI, Address to the Jesuits, 22 April 2006). Yet his was also a restless, unsettled, spirit that was never satisfied. Under the guidance of St Ignatius he learned to unite his restless but also sweet — I would say exquisite — sensibility, with the ability to make decisions. He was a man with great aspirations; he was aware of his desires, he acknowledged them. Indeed for Faber, it is precisely when difficult things are proposed that the true spirit is revealed which moves one to action (cf. Memoriale, 301). An authentic faith always involves a profound desire to change the world. Here is the question we must ask ourselves: do we also have great vision and impetus? Are we also daring? Do our dreams fly high? Does zeal consume us (cf. Ps 68:10)? Or are we mediocre and satisfied with our “made in the lab” apostolic programmes? Let us always remember: the Church’s strength does not reside in herself and in her organizational abilities, but it rests hidden in the deep waters of God. And these waters stir up our aspirations and desires expanding the heart. It is as St Augustine says: pray to desire and aspire to expand the heart. Faber could discern God’s voice in his desires. One goes nowhere without desire and that is why we need to offer our own desires to the Lord. The Constitutions say that: “we help our neighbour by the desires we present to the Lord our God” (Constitutions, 638).

Faber had the true and deep desire “to be expanded in God”: he was completely centred in God, and because of this he could go, in a spirit of obedience, often on foot, throughout Europe and with charm dialogue with everyone and proclaim the Gospel. The thought comes to mind of the temptation, which perhaps we might have and which so many have of condemnation, of connecting the proclamation of the Gospel with inquisitorial blows. No, the Gospel is proclaimed with gentleness, with fraternity, with love. His familiarity with God led him to understand that interior experience and apostolic life always go together. He writes in his Memoriale that the heart’s first movement should be that of “desiring what is essential and primordial, that is, the first place be left to the perfect intention of finding our Lord God” (Memoriale, 63). Faber experiences the desire to “allow Christ to occupy the centre of his heart” (Memoriale, 68). It is only possible to go to the limits of the world if we are centred in God! And Faber travelled without pause to the geographic frontiers, so much so that it was said of him: “it seems he was born not to stay put anywhere” (mi, Epistolae i, 362). Faber was consumed by the intense desire to communicate the Lord. If we do not have his same desire, then we need to pause in prayer, and, with silent fervour, ask the Lord, through the intercession of our brother Peter, to return and attract us: that fascination with the Lord that led Peter to such apostolic “folly”.

We are men in tension, we are also contradictory and inconsistent men, sinners, all of us. But we are men who want to journey under Jesus’ gaze. We are small, we are sinners, but we want to fight under the banner of the Cross in the Society designated by the name of Jesus. We who are selfish want nonetheless to live life aspiring to great deeds. Let us renew then our oblation to the Eternal Lord of the universe so that by the help of his glorious Mother we may will, desire and live the mind of Christ who emptied himself. As St Peter Faber wrote, “let us never seek in this life to be tied to any name but that of Jesus” (Memoriale, 205). And let us pray to Our Lady that we may be emissaries with her Son.

CELEBRATION OF VESPERS AND TE DEUM ON THE OCCASION OF THE BICENTENNIAL OF THE RE-ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS

CELEBRATION OF VESPERS AND TE DEUM ON THE OCCASION OF THE BICENTENNIAL OF THE RE-ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS

ADDRESS OF POPE FRANCIS

Chiesa del Gesù

Saturday, 27 September 2014

Dear brothers and friends in the Lord,

The Society under the name of Jesus has lived difficult times of persecution. During the leadership of Fr Lorenzo Ricci, “enemies of the Church succeeded in obtaining the suppression of the Society” (John Paul II, Message to Fr Kolvenbach, July 31, 1990) by my predecessor Clement XIV. Today, remembering its restoration, we are called to recover our memory, calling to mind the benefits received and the particular gifts (cf. Spiritual Exercises, 234). Today, I want to do that here with you.

In times of trial and tribulation, dust clouds of doubt and suffering are always raised and it is not easy to move forward, to continue the journey. Many temptations come, especially in difficult times and in crises: to stop to discuss ideas, to allow oneself to be carried away by the desolation, to focus on the fact of being persecuted, and not to see anything else. Reading the letters of Fr Ricci, one thing struck me: his ability to avoid being blocked by these temptations and to propose to the Jesuits, in a time of trouble, a vision of the things that rooted them even more in the spirituality of the Society.

Father General Ricci, who wrote to the Jesuits at the time, watching the clouds thickening on the horizon, strengthened them in their membership in the body of the Society and its mission. This is the point: in a time of confusion and turmoil he discerned. He did not waste time discussing ideas and complaining, but he took on the charge of the vocation of the Society. He had to preserve the Society and he took charge of it.

And this attitude led the Jesuits to experience the death and resurrection of the Lord. Faced with the loss of everything, even of their public identity, they did not resist the will of God, they did not resist the conflict, trying to save themselves. The Society – and this is beautiful – lived the conflict to the end, without minimizing it. It lived humiliation along with the humiliated Christ; it obeyed. You never save yourself from conflict with cunning and with strategies of resistance. In the confusion and humiliation, the Society preferred to live the discernment of God’s will, without seeking a way out of the conflict in a seemingly quiet manner. Or at least in an elegant way: this they did not do.

It is never apparent tranquillity that satisfies our hearts, but true peace that is a gift from God. One should never seek the easy “compromise” nor practice facile “irenicism”. Only discernment saves us from real uprooting, from the real “suppression” of the heart, which is selfishness, worldliness, the loss of our horizon. Our hope is Jesus; it is only Jesus. Thus Fr Ricci and the Society during the suppression gave priority to history rather than a possible grey “little tale”, knowing that love judges history and that hope – even in darkness – is greater than our expectations.

Discernment must be done with right intention, with a simple eye. For this reason, Fr Ricci is able, precisely in this time of confusion and bewilderment, to speak about the sins of the Jesuits. He does not defend himself, feeling himself to be a victim of history, but he recognizes himself as a sinner. Looking at oneself and recognizing oneself as a sinner avoids being in a position of considering oneself a victim before an executioner. Recognizing oneself as a sinner, really recognizing oneself as a sinner, means putting oneself in the correct attitude to receive consolation.

We can review briefly this process of discernment and service that this Father General indicated to the Society. When in 1759, the decrees of Pombal destroyed the Portuguese provinces of the Society, Fr Ricci lived the conflict, not complaining and letting himself fall into desolation, but inviting prayers to ask for the good spirit, the true supernatural spirit of vocation, the perfect docility to God’s grace. When in 1761, the storm spread to France, the Father General asked that all trust be placed in God. He wanted that they take advantage of the hardships suffered to reach a greater inner purification; such trials lead us to God and can serve for his greater glory. Then, he recommends prayer, holiness of life, humility and the spirit of obedience. In 1760, after the expulsion of the Spanish Jesuits, he continues to call for prayer. And finally, on February 21, 1773, just six months before the signing of the Brief Dominus ac Redemptor, faced with a total lack of human help, he sees the hand of God’s mercy, which invites those undergoing trials not to place their trust in anyone but God. Trust must grow precisely when circumstances throw us to the ground. Of importance for Fr Ricci is that the Society, until the last, should be true to the spirit of its vocation, which is for the greater glory of God and the salvation of souls.

The Society, even faced with its own demise, remained true to the purpose for which it was founded. In this light, Ricci concludes with an exhortation to keep alive the spirit of charity, unity, obedience, patience, evangelical simplicity, true friendship with God. Everything else is worldliness. The flame of the greater glory of God even today flows through us, burning every complacency and enveloping us in a flame, which we have within, which focuses us and expands us, makes us grow and yet become less.

In this way, the Society lived through the supreme test of the sacrifice unjustly asked of it, taking up the prayer of Tobit, who with a soul struck by grief, sighs, cries and then prays: “You are righteous, O Lord, and all your deeds are just; all your ways are mercy and truth; you judge the world. And now, O Lord, remember me and look favorably upon me. Do not punish me for my sins and for my unwitting offenses and those that my ancestors committed before you. They sinned against you, and disobeyed your commandments. So you gave us over to plunder, exile, and death, to become the talk, the byword, and an object of reproach among all the nations among whom you have dispersed us”. It concludes with the most important request: “Do not, O Lord, turn your face away from me”. (Tb 3,1-4.6d).

And the Lord answered by sending Raphael to remove the white spots from Tobit’s eyes, so that he could once again see the light of God. God is merciful, God crowns with mercy. God loves us and saves us. Sometimes the path that leads to life is narrow and cramped, but tribulation, if lived in the light of mercy, purifies us like fire, brings much consolation and inflames our hearts, giving them a love for prayer. Our brother Jesuits in the suppression were fervent in the spirit and in the service of the Lord, rejoicing in hope, constant in tribulation, persevering in prayer (cf. Rom 12:13). And that gave honour to the Society, but certainly not in praise of its merits. It will always be this way.

Let us remember our history: “the Society was given the grace not only to believe in the Lord, but also to suffer for His sake” (Philippians 1:29). We do well to remember this.

The ship of the Society has been tossed around by the waves and there is nothing surprising in this. Even the boat of Peter can be tossed about today. The night and the powers of darkness are always near. It is tiring to row. The Jesuits must be brave and expert rowers (Pius VII, Sollecitudo omnium ecclesiarum): row then! Row, be strong, even against a headwind! We row in the service of the Church. We row together! But while we row – we all row, even the Pope rows in the boat of Peter – we must pray a lot, “Lord, save us! Lord save your people.” The Lord, even if we are men of little faith, will save us. Let us hope in the Lord! Let us hope always in the Lord!

The Society, restored by my predecessor Pius VII, was made up of men, who were brave and humble in their witness of hope, love and apostolic creativity, which comes from the Spirit. Pius VII wrote of wanting to restore the Society to “supply himself in an adequate way for the spiritual needs of the Christian world, without any difference of peoples and nations” (ibid). For this, he gave permission to the Jesuits, which still existed here and there, thanks to a Lutheran monarch and an Orthodox monarch, “to remain united in one body.” That the Society may remain united in one body!

And the Society was immediately missionary and made itself available to the Apostolic See, committing itself generously “under the banner of the cross for the Lord and His Vicar on earth” (Formula of the Institute, 1). The Society resumed its apostolic activity of preaching and teaching, spiritual ministries, scientific research and social action, the missions and care for the poor, the suffering and the marginalized.

Today, the Society also deals with the tragic problem of refugees and displaced persons with intelligence and energy; and it strives with discernment to integrate the service of faith and the promotion of justice in conformity with the Gospel. I confirm today what Paul VI told us at our 32nd General Congregation and which I heard with my own ears: “Wherever in the Church, even in the most difficult and extreme situations, in the crossroads of ideologies, in the social trenches, where there has been and there is confrontation between the deepest desires of man and the perennial message of the Gospel, Jesuits have been present and are present.” These are prophetic words of the future Blessed Paul VI.

In 1814, at the time of the restoration, the Jesuits were a small flock, a “least Society,” but which knew how to invest, after the test of the cross, in the great mission of bringing the light of the Gospel to the ends of the earth. This is how we must feel today therefore: outbound, in mission. The Jesuit identity is that of a man who loves God and loves and serves his brothers, showing by example not only what he believes, but also what he hopes, and who is the One in whom he has put his trust (cf. 2 Tim 1:12). The Jesuit wants to be a companion of Jesus, one who has the same feelings of Jesus.

The bull of Pius VII that restored the Society was signed on August 7, 1814, at the Basilica of Saint Mary Major, where our holy father Ignatius celebrated his first Mass on Christmas Eve of 1538. Mary, Our Lady, Mother of the Society, will be touched by our efforts to be at the service of her Son. May she watch over us and protect us always.

From: INTERVIEW WITH POPE FRANCIS

From: INTERVIEW WITH POPE FRANCIS

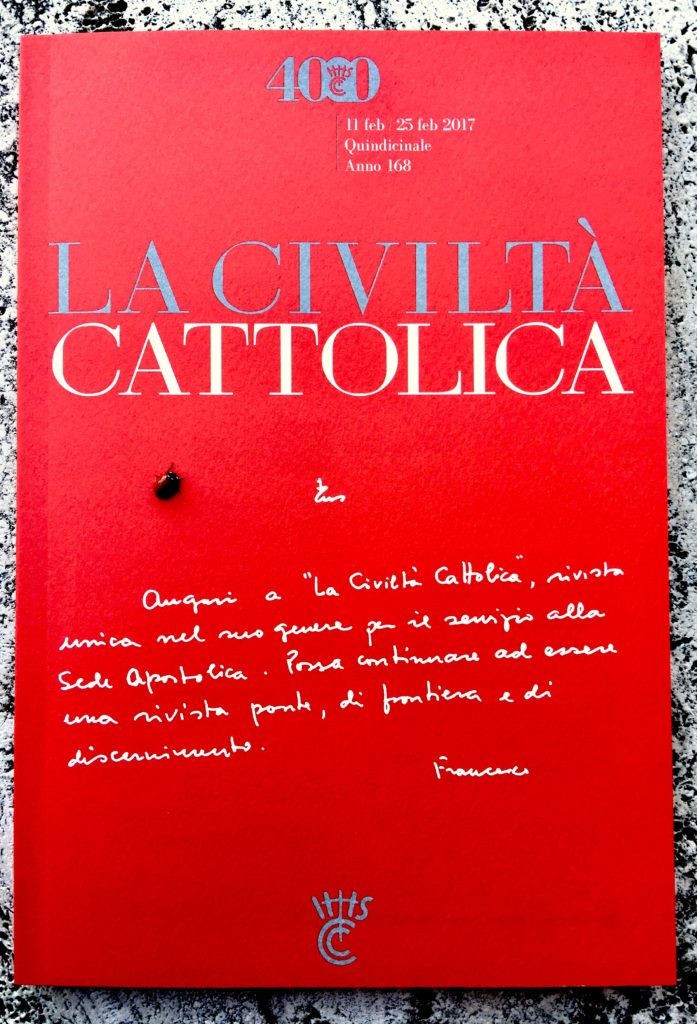

by Fr Antonio Spadaro for the cultural reviews of the Society of Jesus

Discernment is therefore a pillar of the spirituality of Pope Francis. It expresses in a particular manner his Jesuit identity. I ask him then how the Society of Jesus can be of service to the church today, and what characteristics set it apart. I also ask him to comment on the possible risks that the Society runs.

“The Society of Jesus is an institution in tension,” the pope replied, “always fundamentally in tension. A Jesuit is a person who is not centered in himself. The Society itself also looks to a center outside itself; its center is Christ and his church. So if the Society centers itself in Christ and the church, it has two fundamental points of reference for its balance and for being able to live on the margins, on the frontier. If it looks too much in upon itself, it puts itself at the center as a very solid, very well ‘armed’ structure, but then it runs the risk of feeling safe and self-sufficient. The Society must always have before itself the Deus semper maior, the always-greater God, and the pursuit of the ever greater glory of God, the church as true bride of Christ our Lord, Christ the king who conquers us and to whom we offer our whole person and all our hard work, even if we are clay pots, inadequate. This tension takes us out of ourselves continuously. The tool that makes the Society of Jesus not centered in itself, really strong, is, then, the account of conscience, which is at the same time paternal and fraternal, because it helps the Society to fulfill its mission better.”

The pope is referring to the requirement in the Constitutions of the Society of Jesus that the Jesuit must “manifest his conscience,” that is, his inner spiritual situation, so that the superior can be more conscious and knowledgeable about sending a person on mission.

“But it is difficult to speak of the Society,” continues Pope Francis. “When you express too much, you run the risk of being misunderstood. The Society of Jesus can be described only in narrative form. Only in narrative form do you discern, not in a philosophical or theological explanation, which allows you rather to discuss. The style of the Society is not shaped by discussion, but by discernment, which of course presupposes discussion as part of the process. The mystical dimension of discernment never defines its edges and does not complete the thought. The Jesuit must be a person whose thought is incomplete, in the sense of open-ended thinking. There have been periods in the Society in which Jesuits have lived in an environment of closed and rigid thought, more instructive-ascetic than mystical: this distortion of Jesuit life gave birth to the Epitome Instituti.”

The pope is referring to a compendium, formulated in the 20th century for practical purposes, that came to be seen as a replacement for the Constitutions. The formation of Jesuits for some time was shaped by this text, to the extent that some never read the Constitutions, the foundational text. During this period, in the pope’s view, the rules threatened to overwhelm the spirit, and the Society yielded to the temptation to explicate and define its charism too narrowly.

Pope Francis continues: “No, the Jesuit always thinks, again and again, looking at the horizon toward which he must go, with Christ at the center. This is his real strength. And that pushes the Society to be searching, creative and generous. So now, more than ever, the Society of Jesus must be contemplative in action, must live a profound closeness to the whole church as both the ‘people of God’ and ‘holy mother the hierarchical church.’ This requires much humility, sacrifice and courage, especially when you are misunderstood or you are the subject of misunderstandings and slanders, but that is the most fruitful attitude. Let us think of the tensions of the past history, in the previous centuries, about the Chinese rites controversy, the Malabar rites and the Reductions in Paraguay.

“I am a witness myself to the misunderstandings and problems that the Society has recently experienced. Among those there were tough times, especially when it came to the issue of extending to all Jesuits the fourth vow of obedience to the pope. What gave me confidence at the time of Father Arrupe [superior general of the Jesuits from 1965 to 1983] was the fact that he was a man of prayer, a man who spent much time in prayer. I remember him when he prayed sitting on the ground in the Japanese style. For this he had the right attitude and made the right decisions.”

A private encounter of Pope Francis with some Polish Jesuits

A private encounter of Pope Francis with some Polish Jesuits

July 30, 2016

I want to add something now. I ask you to work with seminarians. Above all, give them what you have received from the Exercises: the wisdom of discernment. The Church today needs to grow in the ability of spiritual discernment. Some priestly formation programs run the risk of educating in the light of overly clear and distinct ideas, and therefore to act within limits and criteria that are rigidly defined a priori, and that set aside concrete situations: «you must do this, you must not do this.». And then the seminarians, when they become priests, find themselves in difficulty in accompanying the life of so many young people and adults. Because many are asking: «can you do this or can you not?». That’s all. And many people leave the confessional disappointed. Not because the priest is bad, but because the priest doesn’t have the ability to discern situations, to accompany them in authentic discernment. They don’t have the needed formation. Today the Church needs to grow in discernment, in the ability to discern. And priests above all really need it for their ministry. This is why we need to teach it to seminarians and priests in formation: they are the ones usually entrusted with the confidences of the conscience of the faithful. Spiritual direction is not solely a priestly charism, but also lay, it is true. But, I repeat, you must teach this above all to priests, helping them in the light of the Exercises in the dynamic of pastoral discernment, which respects the law but knows how to go beyond. This is an important task for the Society. A thought of Fr. Hugo Rahner has often struck me[2]. He thought clearly and wrote clearly! Hugo said that the Jesuit must be a man with the nose for the supernatural, that is he must be a man gifted with a sense of the divine and of the diabolical relative to the events of human life and history. The Jesuit must therefore be capable of discerning both in the field of God and in the field of the devil. This is why in the Exercises St Ignatius asks to be introduced both to the intentions of the Lord of life and to those of the enemy of human nature and to his lies. What he has written is bold, it is truly bold, but discernment is precisely this! We need to form future priests not to general and abstract ideas, which are clear and distinct, but to this keen discernment of spirits so that they can help people in their concrete life. We need to truly understand this: in life not all is black on white or white on black. No! The shades of grey prevail in life. We must them teach to discern in this grey area.

The Pope spoke to parish priests, that is, to pastors who have their hands in everything and who know well the concrete situations of people. No one knows the varied reality of life better than they do.

The Pope spoke to parish priests, that is, to pastors who have their hands in everything and who know well the concrete situations of people. No one knows the varied reality of life better than they do.